An educational battle

An assessment puts countries in their place

Photo by: http://visual.ly/america-meet-china

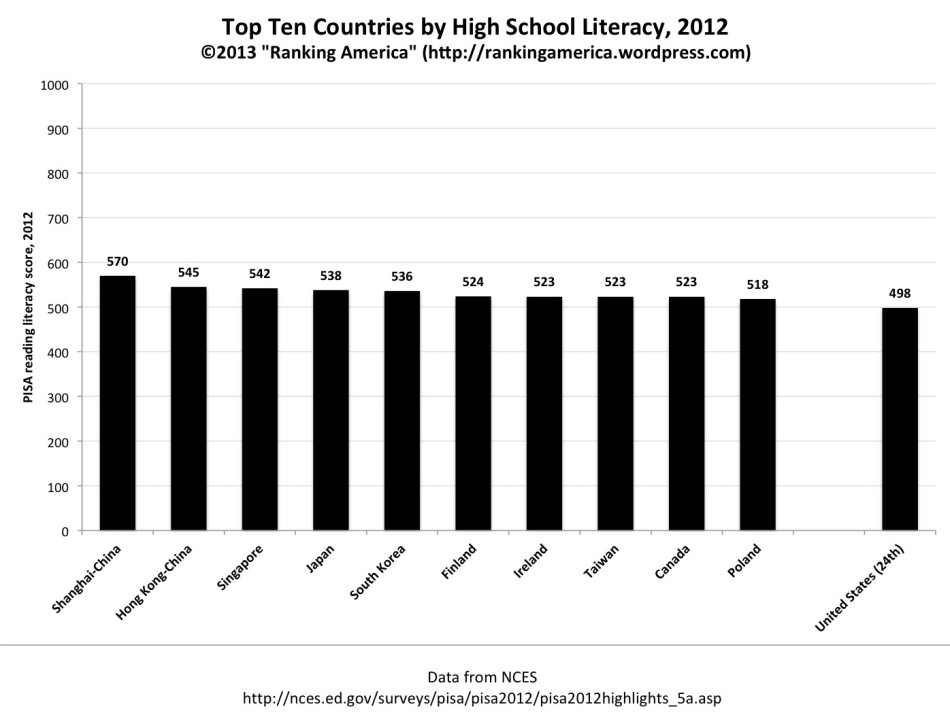

U.S. ranks 24th out of 65 in reading literacy receiving the score of 498 out of 1000.

Every three years, the National Center of Education Statistics looks over every country’s score for the Programme of International Student Assessment Test, better known as the PISA Test. Each randomly selected child from every country is tested on science, reading, and mathematical literacy. The test is administered to a sample group consisting of 15 year-olds. For the year 2012, the United States ranked 24th for reading literacy, 36th for mathematical literacy, and 28th for science literacy, according to NCES.

The PISA Test was first administered in 2000 and has continued ever since.

“PISA is coordinated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a member organization of industrialized countries. The countries that participate in PISA agree on what will be assessed, and contribute and review all assessment questions before the assessment is administered,” said PISA coordinator Kelly Dana. Because not every 15 year-old in each country is used as a sample, there is a specific process used to collect a group of kids. The aim is to get a group that represents the entire country’s population of 15 year-olds. Each country or education system submits a sampling frame and a minimum of 50 schools are sampled. 150 kids are selected randomly from the frame and 65 percent of the schools within the frame must be selected. A list of all eligible kids from each school get sent to the Australian Council for Educational Research, ACER, and 80 percent of these listed students must participate for the scores to be reported to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

In each section, questions are both multiple choice and open-ended.

“Each student takes a two hour assessment. It is timed so that it is administered in a standardized manner across countries, but it is not designed to be speeded,” said Dana. The purpose behind this test is to assess the amount of knowledge that students have kept with them.

“PISA examines the extent to which students near the end of compulsory education have acquired some of the knowledge and skills that are essential for full participation in modern society,” said Dana.

Starting from the 2003 PISA Test scores, math, reading, and science literacy have slowly fallen in their ranking in the United States.

“American education is a mile long and an inch deep. We’re cramming information and focusing on names and dates, which are harder to recall,” said assistant principal of Potomac Falls High School Kirk Dolson. America’s education is run much differently compared to other countries around the world.

“Other countries focus on critical thinking and problem solving. They also separate genders, causing fewer distractions. However, girls aren’t exposed to as much math or science,” said Dolson. Even so, countries such as Japan, Finland, Poland, and Canada are far ahead of the United States. The section our nation is falling the most in is mathematical literacy.

“Our goal is to have students leave with Algebra I by eighth grade, thus we can offer more varying advanced mathematics courses before leaving high school. If you complete an AP math class [anything beyond Algebra II] in high school, statistics show us that almost all those students go off to college and eventually complete their four years,” said Director of Loudoun County Public Schools David Spage.

The PISA Test gives each country valuable information about whether or not their teaching practices are affective.

“In my opinion, tests like the PISA and other standardized and norm reference tests, when used properly with good data analysis, can offer cohorts of teacher’s information about their instruction. If they can get themselves to a mindset of growth with that information, that’s where we’ll see change,” said Spage. Even though our scores are becoming less and less impressive every three years, our nation, our states, and our counties seem reluctant to change teaching values, practices, or techniques.

“We may be testing some students who maybe aren’t necessarily on an advanced college track, while they [other countries] are only testing students who are,” said Spage. With a worldwide test like the PISA, standardized or standard are very relative terms. Teaching strategies to school environments vary extensively when comparing countries to one another.

“We want to see what the PISA can offer us within our own ‘comparing apples to apples’ realm,” said Spage. If we were, as a nation, to make a change, it seems we would have to take baby steps.

“I think the Department of Education nationally will take the PISA results and we’re going to see more policies or incentives as of result of it,” said Spage. So what do these small steps entail? The solution is not simple with an array of possibilities.

“To improve our education, it would have to start at the top, such as colleges or universities. They teach very traditionally there, focusing on memorizing. What we don’t teach well is how to teach yourself how to learn and how to be able to do things for yourself,” said Dolson. With a country as large as the United States, surely the government would have to help implement change.

“The government in our country wants an easy fix. Their focuses are common core standards, therefore, creating a national curriculum,” said Dolson.

This test serves a variety of purposes and its popularity has been growing over the last few years. Whether ranked first or last in any three categories, the PISA Test is a scale to help better our future leaders of any which country.