Ferguson Grand Jury Decision: The Catalyst to New Debates

New discussions after Ferguson police officer receives no indictment

The Ferguson grand jury decided on Nov. 24, 2014, not to indict Darren Wilson, a police officer who shot and killed unarmed 18-year-old African American Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO. Wilson testified that Brown charged and attacked him, but there were conflicting witness reports and unclear audio recordings. Protests ensued and opened many topics up to debate.

Racial inequality?

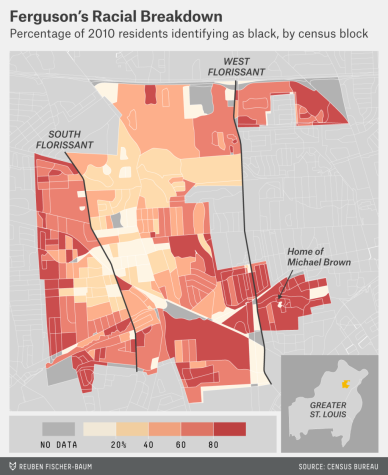

Ferguson and some of its neighboring towns are predominantly black, but St. Louis county is mostly white. The sharp disparity has led to racial tension, especially between the white police force that serves Ferguson. Black Americans have reported unequal treatment, facing harsher treatment and stricter punishment than their white counterparts. These underlying preconceptions lead blacks in not just Ferguson, but around the country, to face more traffic stops and arrests than do white people. Repeatedly shot by a white man who described him as a demon, Brown too may have been a victim of racial profiling.

The Twitter hashtags #BlackLivesMatter and #JusticeforMikeBrown followed immediately after the incident went viral. Twitter users protested against the grand jury decision with millions of tweets under #CrimingWhileWhite and #AliveWhileBlack. White people tagged stories of evading police punishment with the former, and blacks detailed their unequal treatment under the latter.

While many may assume that racial issues are common only in the South and Midwest, students in Potomac Falls find that the problem is prevalent even in Virginia.

“People sometimes look down on you. They automatically assume I’m less[of a person] because I’m mixed,” said sophomore Chantal Groot. “One time I was in my dad’s house and his co-worker was over. He thought I was the maid.”

Freshman Riley Evans recalls how her classroom was set up when she lived in West Virginia during middle school. Her teacher separated the class by race. “The entire back corner of the room was all the black and Hispanic kids, and the Asian kids were in front of them. The white kids got the good side of the room with the good views. And he would never call on anyone who wasn’t white.”

Body Cameras for Police?

To avoid a similar problem with ambiguous audio recordings, body cameras were offered as a potential solution to make all altercations transparent.

“I think [body cameras] will help,” said Evans, “But, it shouldn’t be a [rule] that they should have to wear body cameras. They should just not lie in general.”

This investment seemed worth the cost to many until another recent incident: Eric Garner, an unarmed African American, died from asphyxiation caused by a chokehold by an NYPD officer, and the whole incident was caught on video by a bystander. The bystander was the only person arrested.

“With Eric Garner, I think it’s proven that body cameras aren’t an absolute solution as many people thought it would be,” said senior Noah Black. “Police need to be properly educated and trained about how to deal with civilians.” In light of the Garner incident, the NYPD held a three-day retraining period on the proper use of force during confrontations. Additionally, Black suggests that “People need to be educated about how to interact with police. It’s a two-way street.”

Jury of his peers?

While police education and retraining may prevent further incidents, the grand jury in Ferguson had to resolve the situation at hand. The grand jury was composed of nine whites and three blacks. Nine votes in favor were required to indict Wilson.

“So right there, you have a nine majority,” said sophomore Neil Pillai. To Pillai, “it’s inevitable,” that racial biases will come into play.

The racial composition in Ferguson is 67% black and 29% white, according to Forbes Magazine. The grand jury, 75% white with nine white jurors, was not demographically representative of Ferguson in regard to race.

“How was the voice of the African American person ever going to be heard if already you had the majority going into it?” said CTE teacher Jessica Rettle. “I feel the odds were stacked [against Brown] when the jury was created.”

Protests in Ferguson followed the final grand jury decision, and the movement spread around the country, most notably in New York City and Washington D.C. Riots in Ferguson have escalated to protesters looting and burning buildings with police retaliating with tear gas and plastic bullets.

While students at PFHS are also passionate about the decision, junior Malik Crowe says, “[the protesters] shouldn’t be burning down buildings. Everybody thinks we’re already bad people, so this just makes us look worse.”

Police reform needed?

The Ferguson shooting brought attention to more instances of police brutality: the aforementioned NYPD incident with Garner, and more recently, the shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice by Cleveland police as Rice was suspected of dangerous activity because of the toy gun he carried. Because there was no indictment issued against the police for Brown or Garner, Rice’s family initially tried to bypass a grand jury to get a direct indictment because they feel the grand jury process unfairly favors cops.

“Public service needs to be held to a higher moral standard than they are currently,” said Black. “We need to restructure the way police officers are prosecuted. Police officers shouldn’t be prosecuted by a local attorney; they should be prosecuted by a federally assigned attorney who specializes only in that case.” Under federal jurisdiction, cases against police officers could be investigated at a national level to eliminate local pressures.

A reorganization of authority at the national or local level could accomplish these goals.

“Look at the government and the police force that is running a town that is predominantly black,” said Rettle. There are three black officers on the police force of 53 in Ferguson, a town that is 67% black.

“We need to make sure our government is representative of the people that are being served,” said Rettle.

There is a clear racial and economic divide in Upper Saint Louis. The median household income in Florissant is $51,529, but only $37,000 in Ferguson. Rettle lived in Florissant, the sister city to Ferguson, from 1975 through her high school graduation in 1992, and she returned from 1996 to 1998. She recalls her experiences living between the two distinctly racially separated areas.

“My best friends lived two minutes away from me, and that was in Ferguson. [I lived] right on the border. There was a little town right in between us, and it was small, but we knew that if we were driving down the main road, Florissant Road, we had to put our cruise control on because the cops were going to get you. Overwhelmingly, my black friends would get stopped more than I would. So is there racial profiling? Do these things exist there? Yes, they do.”